You may have heard that the reason Bruce Fanjoy won the recent election in the riding of Carleton was because "the government" redrew the electoral boundaries with partisan considerations in mind.

This is laughably wrong, for two reasons.

Reason 1: "The government" doesn't draw the boundaries of federal ridings. Ten independent commissions – one for each province – are appointed after each decennial census (held in years which end in -1). It is these commissions which redraw the electoral maps.

The process of apportioning the seats among the provinces, and of period redrawing of the electoral boundaries to keep pace with changes in population geography, are well-explained by a Library of Parliament publication titled, curiously enough, The Process for Readjusting the Seat Count in the House of Commons and the Boundaries of Electoral Districts.

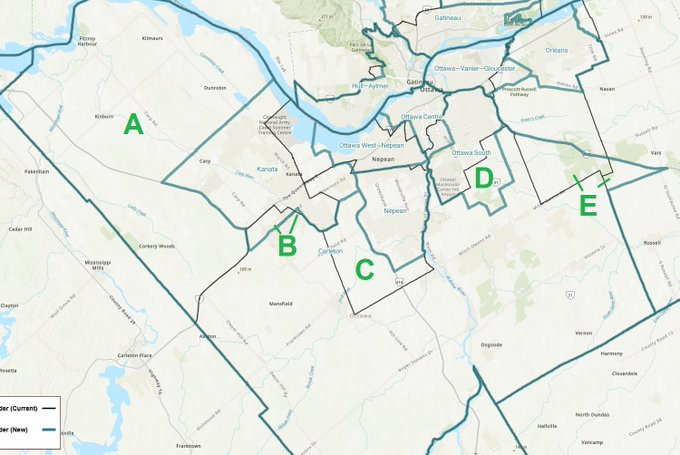

For reference, the former boundaries of Carleton and other Ottawa-area ridings, in effect for the general elections of 2015, 2019, and 2021, looked like this.

For further reference, the commission's 2022 initial proposal looked like this. There would have been four urban and suburban ridings, including Carleton, entirely contained within Ottawa city limits.

There would also have been three mostly-rural ridings, east and west of Ottawa city limits, which would have seen their boundaries skwoonshed (technical term) to take in the remaining rural township areas of amalgamated Ottawa that were not already in Carleton.

After a process involving public hearings, written submissions, and opportunities for incumbent Members of Parliament to state their objections or concerns, the commission published their final revision in 2023. The Ottawa-area ridings would now look like this.

The western rural riding "skwoonsh" into the former townships was rejected in favour of merging those areas into Carleton. It is also worth noting that the former Member for Carleton did not file any objections when the boundary proposal came before a House of Commons committee.

Reason 2: The riding boundary changes as published in 2023, and in effect for the 2025 general election, made the riding of Carleton, everything else being equal *more likely to elect a Conservative candidate*.

"Everything else being equal" means, imagine a world in which everyone who voted in 2021 were to vote again, for candidates of the exact same party, but using the 2025 riding boundaries. It's not hard to imagine: this is the premise of a thing called The Transposition.

After the decennial redistribution, Elections Canada transposes the previous results by party into the new boundaries. The latest transposition is available here, with data.

Explained visually, here's what happened with Carleton and its neighbours. Blue lines are the new boundaries. Black lines are the former ones. There are five main areas, lettered here A through E, where territory and population was redistributed from one riding to another.

There were also a handful of very minor boundary adjustments in the final boundary descriptions, which resulted in unpopulated bits of land moving around; we can ignore those.

Now, let’s take the major changes one by one, starting with A. The area outlined in yellow is was transferred from Kanata to Carleton. The thin lines show polling division ("poll") boundaries. The coloured dots show the winner of that poll (Conservative blue, Liberal red).

The size of each coloured dot corresponds to the number of votes cast in that poll. These rural polls transferred from Kanata to Carleton didn't hurt the Conservative campaign in Carleton. Everything else being equal, they would have helped it.

Here's B. The large chunk outlined in yellow is an area of Stittsville which was transferred from Carleton to Kanata. In 2021 it was roughly a wash, with both Conservative- and Liberal-voting polls.

There was also a small triangular zone in the top right of this map, consisting of roughly 1.5 polling divisions which voted Liberal in 2021, which was moved from Kanata to Carleton.

In area C, four rural polls were transferred in whole or in part from the adjacent riding of Nepean. This area voted Conservative in 2021. (The one Liberal-red dot at the top shows the result in that poll, but the transferred portion of that poll is itself unpopulated.)

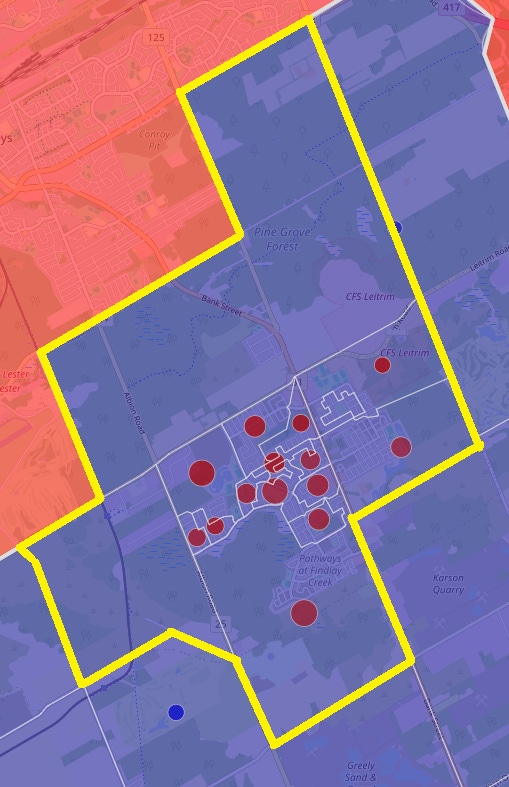

In area D, the suburban-exurban area in and around Findlay Creek and Leitrim was moved out of Carleton and into Ottawa South. In 2021, and the preceding two elections, this area voted Liberal.

And in area E, three rural, Conservative polls were transferred into Carleton from Orleans, as well as a lightly-population portion of another Conservative-leaning poll from the former riding of Glengarry–Prescott–Russell.

In sum: the changes to the boundaries of Carleton in areas A, C, and E net-*added* Conservative voters to the riding. The changes in area D net-*removed* Liberal voters. And the changes in B, around Stittsville, were very approximately neutral in impact.

The 2021 poll-by-poll maps above are screen-capped and annotated after the originals which are published by the very great Canadian behind the switches at the Election Atlas.

So, everything else being equal, the changes to Carleton's riding boundaries, as set forth by an independent commission following an established process in effect since the 1960s, *benefitted* the former Conservative incumbent.

Indeed, the real-world result in 2021 in Carleton was 49.9% to 34.4 for the Conservative candidate over the Liberal. The 2021 vote, using the vote transposed into the 2025 Carleton boundaries, would have been 51.9% to 31.9, widening the Conservative margin by 5%. 26/n

There would have been almost no incumbent Member of Parliament happier with the final electoral boundaries map, as established for the recent election, than the former Member for Carleton. A 5% ballot-box bonus. And without even having to work for it.

This appeared original on X/@labradore in the wake of criticism of the results in Carlton where Pierre Poilievre lost a seat he had held since 2004. It is reproduced here with permission and minor editing.

A closer examination reveals that this perspective overlooks critical factors that likely impacted the election outcome.

1. Boundary Changes Significantly Altered the Riding’s Composition

The 2022 federal electoral redistribution brought substantial changes to the Carleton riding. Notably, it lost the suburban neighborhood of Findlay Creek, which had previously voted 60–70% Liberal, and gained rural areas from Kanata-Carleton, traditionally Conservative strongholds. While these changes might appear to balance out, the addition of new areas introduced voters unfamiliar with Poilievre, potentially affecting his support base. Moreover, the redistribution’s timing meant that Poilievre had limited opportunity to engage with these new constituents before the election.

2. The 90-Candidate Ballot Introduced Unprecedented Complexity

The presence of 91 candidates on the Carleton ballot, a record in Canadian federal elections, was not a mere coincidence. This “Longest Ballot” initiative aimed to protest the first-past-the-post system by overwhelming the ballot. While the total votes for independent candidates were relatively low, the sheer number of names could have caused confusion among voters, potentially leading to ballot errors or voter fatigue. Such factors, while difficult to quantify, can influence election outcomes, especially in closely contested ridings.

3. National Vote Share vs. Seat Distribution Highlights Systemic Issues

Nationally, the Conservative Party secured approximately 41.27% of the popular vote in 2025, surpassing the vote shares that led to majority governments in previous elections (e.g., Jean Chrétien’s 38.5% in 1997 and Stephen Harper’s 39.6% in 2011). Despite this, the Conservatives did not form the government, underscoring the disparities inherent in the first-past-the-post system. This discrepancy between popular vote and seat allocation suggests that structural factors, beyond individual candidate appeal, play a significant role in election outcomes.

While voter sentiment undoubtedly influences election results, it’s essential to acknowledge the structural elements—such as boundary redistributions and ballot design—that can significantly impact outcomes. In the case of Carleton, these factors likely played a role in Pierre Poilievre’s defeat, and dismissing them oversimplifies the complexities of electoral dynamics.

the process is heavily influenced by public submissions—often orchestrated by political parties trying to shape outcomes in their favour. In Carleton, Liberal-aligned groups absolutely pushed for boundary changes that diluted Conservative strongholds by adding suburban and rural areas with different voting patterns. That’s political strategy 101—done through “independent” processes but driven by partisan advocacy.