Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.

George Orwell, Nineteen eighty-four.

Years ago, in university, I bumped into a friend of mine who was enrolled in a music composition course. We chatted, talked about what he was working on, and as the conversation got rolling, he pulled me into a practice room, lifted the cover off the keys on the small upright piano there, and gave me a sample of his composition.

"What's it called?" I asked.

"That's the problem," he shot back in obvious frustration. "I have no idea." I asked what he'd been thinking about when he wrote the piece and it all made sense with the technical choices he made of chords, melodies, and so on. He described transitions musically so I suggested he call it Liminal Spaces.

That was a new phrase to me at the time and while he hadn't been able to come up with a simple musical piece with a beginning, variations in the middle, and resolution at the end in the stereotypical format of the assignment, he had all the bits there in an unconventional way. The word "liminal" fit with what he was doing and with the sense he had no name for it.

Liminal means "occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold." It comes from the Latin word limen, which means threshold. Liminal: in between. In English, it also means "relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process." Like the end or start of a project or maybe a relationship.

In there is the idea of being unsettled or unresolved. Whatever is going on is not one thing or the other. It's in between. In the middle of that change, in the transition, or in the translation - in the sense of physical shifting like a helicopter going from vertical to horizontal motion - the translation from one form to another, you can see and understand what used to be or what's ending and hasn’t quite finished yet because that's where we've come from.

We can see where we are.

But looking ahead, things can be uncertain which means they can be scary sometimes. We have no idea what's going to happen next or what shape "Next" will take. Liminal is like limbo but the difference is the sense of change that comes with liminal. And from our perspective in that transition, we cannot see clearly enough of what is coming to understand what the path ahead looks like.

We just know it's coming.

There’s nothing unsettled or unresolved about Bond Papers. Become a paying subscriber to find out what’s going on and where we are headed.

We tend to think of uncertain times as bad. Lose a job. Marriage breaks up. Kids move out. Partner dies. But transitions can be positive. Just look at the flip of all of those negative things: get a new job. Fall in love, get married, have a child, especially the first one. There is an equal sense of purpose and direction even if the direction is not clearly seen at first.

This column came together about two or three months ago. Wednesday’s column came together Tuesday. What’s behind both is the sense that what we are seeing politically these days repeats or derives from what went before even though the situation compared to 40, 25, or even 10 years ago is quite different. And in a sense, what we saw from Danny Williams and the Pea Seas went back to the 1970s as if the intervening 30 years never happened. There is conservative and then there is just pretending the very different is just the same.

But what’s different now especially and perhaps the sense we can trace back about 20 years is that there seems to be no direction or purpose to what’s happening. In the 1970s through to the 1990s, we wanted to be a have province - one that doesn’t get equalization. We wanted to be wealthy and prosperous like other Canadians. We wanted Canadians not to look down on us as poor and stupid, not to make fun of us and call us Newfies.

We don’t seem to have any sense of where things are going anymore. There’s no goal. No purpose. No point. And we call ourselves Newfies now and do all the things we once thought were embarrassing and demeaning. We wanted to stand on our own and run our own business without help. These days, when governments are handing out firefighting equipment and making it sound like the cure for cancer, we are begging Ottawa for cash because we are broke.

People go through transitions so it makes sense to think societies go through the same thing. The Weimar Republic in Germany after the Great War until the Nazis took power in 1933 or Germany in the period of the end of the second war until the creation of a West German state and an East German state. Closer to home. Newfoundland from the early 1920s until the end of self-government in early 1934 or from the end of the second war until Confederation in 1949. Transitional times. Extended periods when one way of being ended and a new one was starting.

There can be a difference in how long those liminal periods last. Newfoundland started to come unhinged in 1917 when Edward Morris left for England permanently and the government went into the hands of a coalition. Through the 1920s, the country staggered along through Richard Squires’ scandals to the government’s steadily worsening financial state, the rise of fascist beliefs in the elites, then financial collapse and finally the surrender of self-government in 1933.

The second liminal period was much shorter: 1945 or thereabouts until 1949. The British were keen to get Newfoundland running itself again and the locals could not wallow in indecision as they’d done before. The British could nudge, coax, or push change but it was ultimately the people of Newfoundland who decided it and so they opted for Canada because it promised a financial backstop the British would not offer for an independent country.

Newfoundland and Labrador after 1949 wasn’t uncertain about anything. There was life and growth and enormous changes. Jobs, families, the arts, learning, all bloomed. Exploded. And even though Newfoundland and Labrador was in 1989 where it had been in 1949 compared to the rest of Canada, the transformation within Newfoundland and Labrador in those first 40 years was profound.

More importantly, in 1989 we were just at the front end of what would become the fulfillment of a national dream in Newfoundland and Labrador of not being merely at the bottom end of Canadian lists but being a province that could stand on its own, that was wealthy as any other place and perhaps wealthier than most. This had been a political goal for a very long time, one that cut across party lines and in the early 2000s it came true.

A dozen years ago, historian Jerry Bannister asked the question of what now given that Newfoundland history was finished. His question came from Francis Fukuyama’s book about the end of history, poking fun at Marx, when the Soviet Union vanished, the eastern European bloc collapsed, the Berlin Wall fell and western liberalism triumphed. Now that we are a have province and we’ve built the Lower Churchill, Bannister wondered, now that these national goals of a half century and more had come true, what next in Newfoundland and Labrador?

As much as Bannister sensed that both the MFers - Muskrat Falls backers - and those of us opposed to Muskrat Falls felt we were at a watershed moment, there is now, that dozen years on, a sense that very little has changed. We have not broken through into the future Dunderdale and her colleagues promised when we would no longer lament the lost opportunities of the past and instead would look to a bright and sustainable future.

Even at the time Kathy Dunderdale spoke to the Bored of Trade in 2012 about the need to just get on with Muskrat and stop chewing it over, it was clear that Williams and Dunderdale and their fellow cultists were not breaking with the past at all but merely recycling it, repeating it in the Marxian sense of farce since we’d done the tragedy already in 1969 supposedly. There was also a great deal of hypocrisy in Dunderdale’s speech, which Bannister quotes, since she and Williams had justified all their actions as correcting the mistakes of the past. They were Trumpian in the delusions before we knew what Trump was.

The thing is, the change had already happened and someone else had done it. The have status achieved in 2009 was done before 2003. Time is linear to put it another way and yet Williams and Dunderdale were circular in their rhetoric and reasoning. In 2010, they told us they’d broken the Quebec stranglehold even though they’d told us they’d done that the year before in another announcement and in truth, someone else had actually done it in the United States a decade before that, at least.

As much as many expected 2015 would bring more than just a swap-out of elites, we’ve had just about everything recycled as in the Danny years. Ending our dependence on oil became doubling oil production. We are fighting with Ottawa for Equalization and in the more recent iterations no later than Tuesday this week, Andrew Furey is sounding like a federal Liberal tackling Pierre Poilievre even though Furey’s policies and rhetoric often sound like they are more lined up with Pierre than agin him. Even in that, Furey is even Dr. Doolittle with pushme-pullyou contradictory statements and policies as he sounds like a federal Liberal, not someone trying to slide away from their brand.

Times of great change often trigger explosions of creativity and passion and debate. What happened in Newfoundland and Labrador after Confederation included painting, plays, music, writing, all reflecting the social and economic upheaval across the new province. Think here of David Blackwood’s paintings, Tom Cahill’s play about Confederation, Horwood’s books like Tomorrow will be Sunday, Codco, Figgy Duff, Ray Guy, or the steady flow from both professional and amateur researchers of non-fiction on local history, language, and culture. Not all of it by Newfoundlanders and Labradorians either - Michael Cook’s Head, guts, and sound bone dance is but one example - but all clearly rooted in the people and the place and the changes they were going through.

Some of the arts themselves were new, something chosen as a means of expressing the feelings and ideas brought on by the transition. Much of it did not celebrate the change. Read Jeff Webb’s most recent book on cultural history in Newfoundland and Labrador and that comes through plainly. The cause of art is the story of visual art in Newfoundland and Labrador after Confederation told chiefly through the political struggles over the development and management of a provincial art gallery.

What is unmistakable though is that the cultural and political dialogue were not only driven by changes, they helped shaped the change. Those struggles both reflected and we're very much part of the larger political struggles within Newfoundland and Labrador over the place, the people, and their future. There was transition. There was change. But unlike today there was also coherence and a sense of direction.

What’s been most striking about the past 20 years by contrast is the silence of the arts and other communities as the province goes through changes no less profound than those of the preceding half century. In place of Codco, we have Republic of Doyle or Son of a Critch, both enormously successful for a local production but that in style and content are just American sit-coms with a Newfie skin. One cannot make out any meaningful difference between Doyle, the new St. Pierre - easily described as Death in Paradise North - or Critch on the one hand and Hudson and Rex, Frontier, or Surreal Estate on the other for their lack of connection to Newfoundland and Labrador beyond the superficial.

It’s not like these more recent Americanized projects are in addition to locally-derived creativity. They’ve replaced it. There isn’t anything else, at least certainly not in the volume we saw before. And even Codco has been absorbed into mainstream Canadian culture and progressively lobotomised until its intellectual and cultural roots are unrecognisable in the still-surviving version of This hour has 22 minutes. CBC really is the place that comedy goes to die.

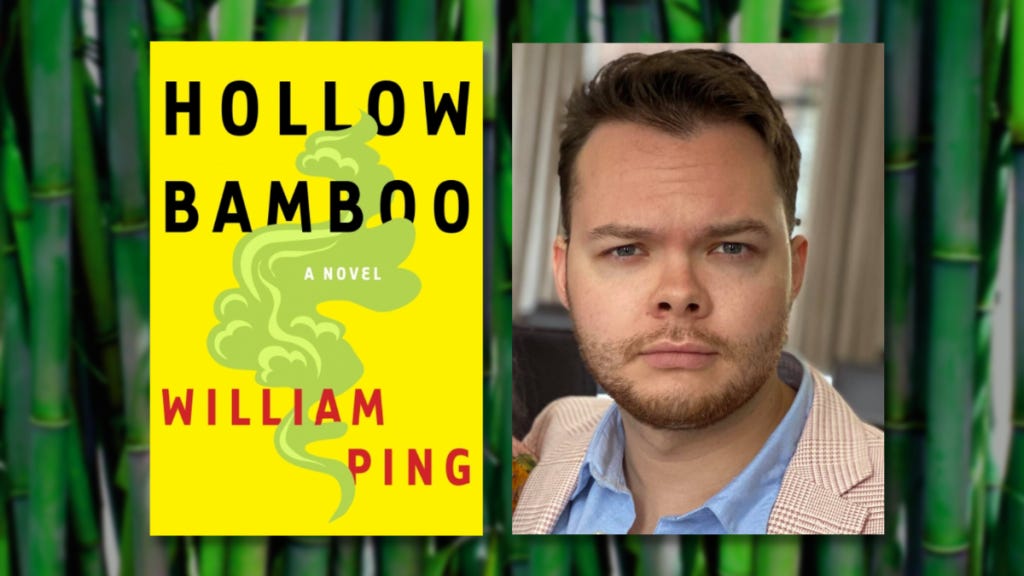

While there is still a thriving publishing scene in Newfoundland and Labrador, much of it is a mixture of nostalgia or, like the TV shows, nothing more than mainland tropes in Newfie garb. There are exceptions. Wayne Johnston remains true to the roots of his earlier work and William Ping’s debut novel is a landmark contribution to both cultural exploration and writing that feels very much like the place about which and the people about whom the book is written. Ping’s work would stand out in any bookshelf but in comparison to other local writing it is radically different.

Academic writing is the same. Jeff Webb’s history from University of Toronto Press of the art gallery and the accompanying cultural and political wrangling stands in stark contrast to two other works published also this year by McGill-Queen’s. Both are New Colonialists or New Mummers, as regular readers will know the terms. Christopher Aylward’s revamped doctoral thesis is not about the Beothuk despite the title but is, in every respect the imposition of modern colonial narratives about Indigenous people on Newfoundland and Labrador. He quite deliberately misrepresents the range of writing about the Beothuk to fit within not merely modern popular Canadian and American tropes about North America’s original people but to align with local Mi’gmaw efforts to erase the Beothuk and rewrite the history of Newfoundland to make the Mi’gmaw something they are not: Indigenous to the island. The result is less history than fiction.

Similarly, Michael Westcott’s book about how the Great War changed Newfoundland manges to avoid the subject entirely by jumping about in time simply to fit his subject within fashionable tropes. It is rare to find a historian who struggles with time, but Westcott is the poster child for the affliction as the book suffers from the worst infections of presentism seen recently. In a book that is ostensibly about gender and class among other things, Westcott actually misses the entire paramilitary religious cadet movement and its ties to concepts of muscular Christianity and social reform.

Westcott’s problem is that he is Americanized in his outlook and Canadianized in his understanding of Newfoundland hence he has no idea, evidently, of the relationship between Newfoundland and Britain before 1949 and misses the voluminous work in Britain on the cadet subject. At least Aylward listed Justice Leo Barry’s 600 page detailed and scholarly destruction of the Mi’gmaw claims to Indigenous status even if he ignored it in the thesis and in the recent book. Westcott shows no signs he knew of the relevant work in the first place.

Germany and Newfoundland in the 20th century were as wildly different countries as you might imagine but for all the differences, they share some curious coincidences in time. Both were broken financially and politically by the Great War although for starkly different reasons. The German surrender and occupation of the country by the Allies - including Newfoundland - the abdication of the Kaiser, the turmoil of Weimar democracy were in some respects matched by Newfoundland through the ‘20s. The coalition government from 1917 carried on in one form or another in the hyperfluid legislature that included the infamous Richard Squires scandal in 1923 as well as the collapse of one government when the finance minister introduced a budget, crossed the floor to the opposition, and voted against his own budget.

Both countries struggled financially in the 1920s and leading elements of both countries turned to fascism or similarly authoritarian ideas as the way out of the predicament. In 1933, the Newfoundland parliament accepted the end of self-government in the country while Germans elected the Nazis and Hitler to a plurality, which was all they needed to seize power.

Both countries emerged from the war that followed transformed, although in radically different ways and for different reasons. German was smashed, divided among the allies, while Newfoundland went into a sort of political hibernation through the 1930s and then only stirred slowly as the Second World War shook the country socially and economically.

Germans call 1945 Stunde Null - Hour Zero - the moment when the war ended and non-Nazi Germany began. It is a way of disconnecting from the past, to pretend that there was no connection between the new Germany and the old one.

In some ways, 1949 is Hour Zero for Newfoundland, the moment time began again, although no one has ever said so publicly. Like so many things about Newfoundland, such a consensus is seldom acknowledged as such. It is just accepted. A fact. The post-Confederation nationalists talked of three great betrayals of Newfoundland by outsiders. It was always outsiders. They repeated the lie from the 1920s that the Governor in 1914 had been a dictator, deciding that Newfoundland would go into the war and driving the government to do what ultimately proved to be disastrous at places like Beaumont Hamel. Then the British betrayed Newfoundland and took away its own government because of the war debt. And in the final act of betrayal, the British engineered Confederation to give beautiful Newfoundland to the Canadians who now supposedly exploit it. None of these things is true but they are, in one way or another still widely accepted.

We see this treatment of 1949 as Hour Zero in other ways. There is a very common phrase these days in both academic and popular circles that Newfoundland before 1949 was a colony of Britain, like Kenya or India or Antigua: run by the British with the locals having little or no responsibility. The Terms of Union include a line that Newfoundland is to be considered for the purposes of the Constitution as if it had always been part of Confederation but this has been taken literally by many who would easily erase what was before Hour Zero.

The past in Newfoundland before 1949 is not merely a foreign and undiscovered country, it is a fiction, a place about which any story may be invented and people will accept it. Aylward and Westcott reflect this Hour Zero thinking as they simply invent a history for the country before 1949 that suits their modern political purposes. This is no different from what their forebears did with the nationalist lies about the Great War, the end of responsible government, and Confederation.

In his book Out of the darkness: the Germans, 1942 - 2022, historian Frank Trentmann recounts the research done by sociologists in the 1950s about German attitudes to the Nazi era. The most common explanation they found was that evil spirits had taken control of the country and allowed Adolph Hitler and the Nazis to rise to power. This sounds ridiculous to modern ears but it is no less ridiculous than the notion in Lisa Moore and Steve Croker’s book on Muskrat Falls in which Moore describes her own attendance at anti-Muskrat protests in 2016 as being “compelled”, although by whom or what she does not explain. Similarly, a mountain of evidence in front of his eyes at the inquiry led Steve Croker to conclude that Muskrat Falls was the product of global capitalism. The boogeyman, in other words.

In the same way, the myth of the 1969 power contract offers a convenient and entirely made-up external devil to take responsibility not for what happened in 1969 but to justify what the inventors of the myth were doing in the 1970s and 1980s by creating the hydro corporation and then pursuing vengeance. The thing is the Lie is now so pervasive, people are so deeply enmeshed in the Lie that they cannot tell what is real and what is fiction.

As we know from Kathy Dunderdale, the Pea Seas started with the plan from the outset to lure Quebec into a deal on the Lower Churchill. They asked for bids and when in 2006 Danny Williams announced the scheme to go-it-alone but with partners his true purpose was to force Quebec into a deal in which they would give up more. His attacks through New Brunswick, the legal cases to the Quebec regulator in 2007, the attempt to break the 1961 lease in 2008, speeches in New York and elsewhere, were all part of an effort to lure Quebec into a trap.

It failed because Quebec turned to alternatives and had no need to play Williams’ childish game. Williams could not build the project and sell it to anyone at all and so, trapped by his outsized ego, Williams and his co-conspirators created the Muskrat Falls scheme to satisfy their own ambitions, gave away billions to Nova Scotia and saddled local taxpayers with a monstrosity all justified because it would supposedly screwed over Quebec.

Not 15 years later and we may well be on the verge of another deal, this time with Quebec. However, as Andrew Furey’s public pronouncements make clear he and his Brain Trust are also trapped inside the Lie and cannot escape from it. Thus even a very good deal for both parties - which could have been settled in a single meeting three years ago - may well die either in Quebec or in Newfoundland or in both because of the difference between the make-believe world of The Lie and the reality that has existed all along.

Who controls the present controls the past.

Who controls the past controls the future.

George Orwell’s best known book appeared in 1949, Newfoundland’s Hour Zero. It is a brilliant and deceptively simply phrase that explains very well what we have been discussing here. This is what happens in Newfoundland and Labrador. On Thursday morning, CBC listeners heard a political science professor from Dalhousie speaking coherently and intelligently about federal politics. Apparently, the CBC is right next to a mid-sized Canadian university with a very large political science department and no one would go one air.

Had they wanted to speak about politics in this province, they’d be really out of luck since there is no one in the political science department at Memorial who is the least bit interested in Newfoundland and labrador politics. There are historians who research local history but only one perhaps will tackle anything after 1949. Most prefer to look at things before 1832, the year self-government started.

The same is true of something as enormous as Churchill Falls and electricity policy. Very few have written anything at all and what there is would be put together into one very slender book. It’s astonishing to realise there is not a single thing of any consequence that has been written about everything from Churchill Falls through Bay d’Espoir to Muskrat and beyond. There are two books in the works about Muskrat but if they never appear we will be left with the Moore and Crocker volume and its fairy tales and the report of the inquiry led by Richard Leblanc.

Leblanc told the lawyers at the inquiry at the outset that he did not want to have any discussion of politics at all. This is bizarre given the project was, from the outset conceived of and pursued relentlessly by politicians for political reasons. This a perfect example of the role of silence and silencing in local society and politics. We do not talk about important things and if we do, we do so in a way that deflects attention from what actually occurred. This is how those who control the present control the past and thereby control the future.

To bring this back around to the start, we seem to be living in a liminal time, one lacking direction or purpose. Politicians talk about Equalization or battle the federal government because they and the people making a living from the bloated government of the last 20 years do not want to change. It is easier to hire more unproductive health bureaucrats, go further in debt and it is better to co-opt homelessness advocates into running useless shelters than talk openly and plainly about the drug emergency on our streets and how best to deal with it.

The people who profited from the bloated spending do not want to talk about the way they and others profited from Muskrat Falls. Ands when anyone talked of changing course, the elites lined up to tell people like the Globe and Mail reporter in 2019 that *any* alternative to what we were doing - without even considering what it might be - would be horrible and unacceptable.

These are all acts of silence and of silencing. It is control of the present to control the past and thereby control the future. The problem is that we are not closer to Hour Zero as we were in, say, 1974 or even 1984. We are arguable around 1924 or perhaps later with 1933 - the real Hour Zero - less than a decade into our future.

This silence all around us is not excusable as a way of rebuilding and getting on with a brighter future, having come through a horrible past. The silence and silencing prevents us from finding the way ahead.

This silence?

It is the stillness of the embalmer’s workroom on the way to the silence of the grave.

Ed, is the Real Zero Hour when we hit the wall on debt? And then the creditors step in and tell us how to spend? AKA 1933 all over again?

We are currently spending 15% of government revenue on interest alone. More than we spend in total on education. Yet no one in government seems the least bit concerned. I guess when the creditors come in and start dictating terms, our government can call them Goldstein, and have their daily Two Minutes of Hate.

No thought required! Victimhood is an easy sell - that and a ‘savior’ from our own feckless choices.