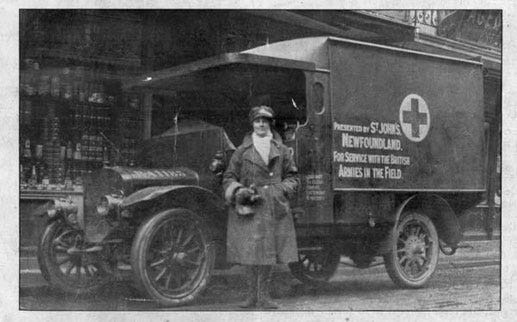

Armine Gosling campaigned to get the vote for women in Newfoundland in the 1920s. Born in Quebec in 1861, she came to St. John’s to teach at Bishop Spencer College, the Church of England girl’s school. In the early 20th century, G…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bond Papers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.