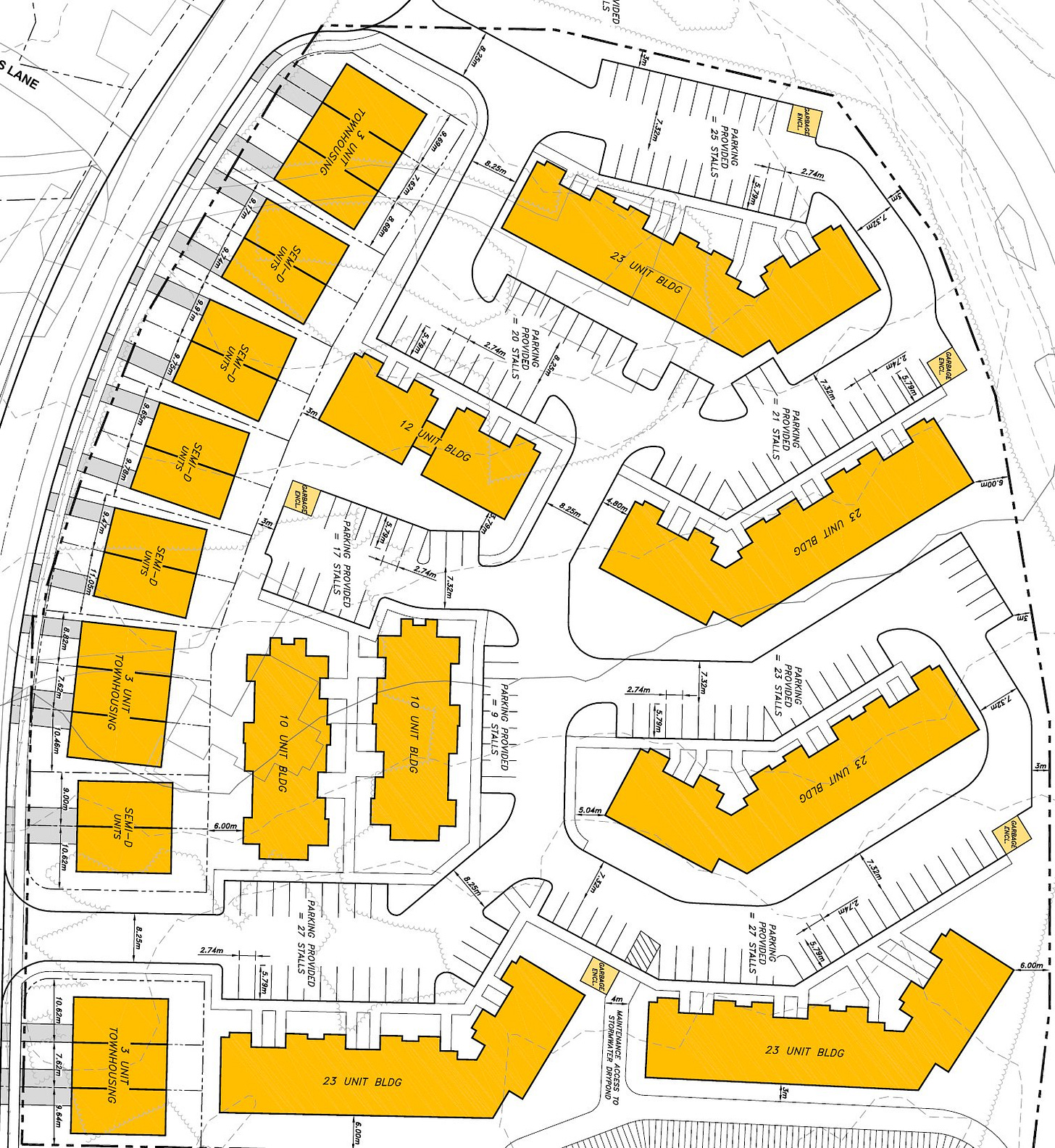

The housing problem: It took the developers of the 147 unit development of apartment buildings and town houses in the north end of St. John’s two and a half years to clear the City’s approvals processes.

The housing problem: A buiness owner an…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bond Papers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.